Tea, Creativity & the Nobel Prize! Meet Dr. Alan Heeger

When you think of people who are ‘creative types,’ do you think of scientists?

When you think of people who are ‘creative types,’ do you think of scientists?

While we appreciate their intense pursuit of answers to questions such as “why did the apple fall from the tree?” not too many of us will put ‘creativity and scientist’ together in conversation. Yet, a great deal of creative energy goes into any scientific discovery. And to prove just that, Nobel Prize winner Professor Alan Heeger’s latest work isn’t an experiment; it’s a book about risk, creativity and discovery in science.

Never Lose Your Nerve! may very well change the way we think about the scientific process and the men and women who dedicate their lives to answering big questions about how and why things work the way they do—and finding novel ways for those answers to make our lives better.

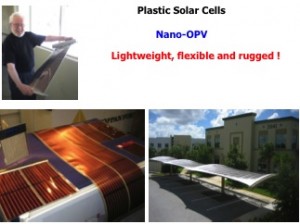

Widely known for his pioneering research in field of Condensed Matter Physics (an interdisciplinary field that merges physics, chemistry, polymer science and biology), Dr. Heeger’s research group at UC Santa Barbara studies the science and technology of semiconducting and metallic polymers with applications for solar panels, biosensors for the detection of specific sequences on DNA, and pharmaceutical technology for targeted drug delivery. In addition to the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, Professor Heeger has won numerous scientific awards and has more than 900 publications in scientific journals. When he’s not working in the lab, Professor Heeger has acted in and produced Broadway plays. He also devotes time to mentoring young scientists.

Pour yourself a cup of Creativitea and find out what insights Dr. Heeger has about risk-taking in the creative and scientific process. We especially like his advise for any person who wants to experience the thrill and satisfaction of a creative life!

You’re working on a book, Never Lose Your Nerve. What’s that title all about?

The underlying theme is the role of Creativity, Discovery and Risk in science. I was moved by Terrence McNally’s play about the great soprano, Maria Callas. Callas had stopped singing and was giving Master Classes to aspiring young women. It was basically a one-woman play; Maria was on stage alone throughout almost the entire performance. At one point, however, a young woman joined her for a Master Class. The young woman sang a few notes, but was then quickly instructed to sit down. There were a few moments of silence after which the young woman asked Callas the question that has remained on my mind and shaped my thinking. She asked Callas: “Why did you stop singing? Did you lose your voice?” Callas responded: “No — I did not lose my voice —I lost my nerve!” Losing one’s nerve will stop creativity and prevent the search for discovery. Losing one’s nerve is “death” to the progress of the scientist or to any creative endeavor.

Tell us more about the chapter, The Delicacy of the Creative Mind.

In that chapter, I compare several examples of mental illness in creative people. Although I have no insight upon which to give advice on how to avoid the potential problems of the delicate creative mind, one must continue to be optimistic about the future and take satisfaction from one’s accomplishments. One must take each day one at a time and seek to make each day meaningful and satisfying.

How do creativity, risk and discovery work together for a scientist?

People typically think of scientists as meticulous and focused, perhaps even boring. Many think that scientists do not tolerate risks. Although true for some scientists, those that are risk-averse are not the creative and productive scientific leaders. In fact, for me and for most scientists, risk-taking is part of our lives; we are “risk-addicted.” Every time we publish an article, we take on risk. We try to make certain that the data are correct, but it is impossible to be certain. We seriously try to give the correct interpretation of the data. But the very process of research involves pushing beyond what was previously known; that process involves taking risks. Of course, the more interesting the result the bigger the associated risk.

Interdisciplinary science is even more risky; the reason is fairly obvious. Educated as a physicist, I have a core of knowledge where I feel very comfortable. Each time I reach out beyond that core, I am exposing my ignorance. But reaching out into new directions involves learning new concepts and finding a way to meld those new concepts into what one had previously known. Exploring new directions is the first step toward creativity and discovery. And dealing with risk is absolutely essential: One must never lose one’s nerve! Additionally, scientific breakthroughs typically result from a combination of creativity and discovery. In science, creativity and discovery are related, but they are not the same.

Tell us about the role of risk and discovery in your scientific life.

Tell us about the role of risk and discovery in your scientific life.

The “discovery” days in late 1976 were among the most perfect days of my life. It is difficult to define the moment of discovery and even more difficult to describe that moment. I recall Alan MacDiarmid, Hideki Shirakawa and I sitting together in my office in the Laboratory for Research in the Structure of Matter (LRSM) at the University of Pennsylvania. Shirakawa had just arrived to work with us as a Visiting Scientist. We invited him to join us because of the beautiful silvery films of the polymer, polyacetylene that he had synthesized.

Based on the infrared absorption data that Shirakawa showed us, I suggested the critical experiment; I postulated that exposure of the pure insulating films of polyacetylene to the vapor of an electron acceptor such as iodine would cause the electrical conductivity to increase to a level approaching that of a metal. Along with Dr. C.K. Chiang, we went to the blackboard and designed a simple apparatus that would enable us to test this idea in a laboratory experiment. Within two days, the data that Shirakawa and Chiang acquired demonstrated that the electrical conductivity had indeed increased by many orders of magnitude.

These were exciting times; the rare times that the scientist hopes for, but rarely experiences. Within a short time, we had polyacetylene samples that exhibited electrical conductivities equivalent to that of lead and mercury (and later even approaching that of copper). Following our initial publications, the number of scientists who initiated research in the field of semiconducting and metallic polymers grew rapidly as people realized the implications for innovative applications. The record of the number of citations that followed from this research is a testament to that. With our discovery of semiconducting and metallic polymers, we created a new field of science at the boundary between Chemistry and Condensed Matter Physics.

Nearly four decades later, the discovery of metallic conductivity in polyacetylene is well known and often used as a highly successful example of the importance of interdisciplinary research. When we started this journey, however, the basic concepts that define semiconducting and metallic polymers were not understood. Even after our initial discoveries were published, such an interdisciplinary endeavor was subject to the risk of being a “bastard child” that would not be accepted by either parent. In 1976, the creation of our truly interdisciplinary collaboration was bold and risky.

We hear you’re a bit of thespian?

I’ve long been interested in and a fan of theatre. I have participated in the production of three Broadway plays: “In the Heights” (2008 Best Musical), “West Side Story” (two-year successful run) and “Barefoot in the Park” (a revival in 2007—it did not survive the critics!).

In Brussels in October 2011, myself ands fellow Nobel Laureate David Gross performed a staged reading of “Copenhagen” at the Centennial celebration of the first Solvay Conference. I played the part of Niels Bohr and Gross played the part of Werner Heisenberg.

Any words of wisdom for young scientists who may be reading?

I work closely with each person individually. When they make a “discovery”—no matter how small—I carefully point out to them that this is indeed a discovery and they should cherish the memory. If you aspire to scientific accomplishments that could have sufficient impact to generate nominations and eventually to result in the award of a future Nobel Prize, I have the following advice:

- Cherish creativity!

- Be bold, and have the audacity to seek to discover!

- Do not lose your nerve.

- Remember that creativity and discovery necessarily involve risk. Dealing with that risk is part of the thrill and satisfaction of living a life in science.

Tags: Alan Heeger, Chemistry, Creative Risk, creativity, Discovery, Nobel Prize, Science